Social Learning, Trust, and Authoritative Data Sources: Part II of results from evaluation of SeaSketch’s predecessor published

From 2012 to 2014, the McClintock lab collaborated with Amanda Cravens, to investigate MarineMap, the predecessor to SeaSketch. A paper describing the second part of the results of that research has just been published:

Cravens, A. E., and N. M. Ardoin. 2016. Negotiating credibility and legitimacy in the shadow of an authoritative data source. Ecology and Society 21(4):30. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08849-210430 (paper link)

MarineMap (a joint project of the McClintock lab, Ecotrust, and The Nature Conservancy) was developed to help participants in California’s multi-year Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA) Initiative decide where to locate marine protected areas (MPAs) along the state’s 840-mile coastline.

Amanda’s study used interviews with users, a participant survey, analysis of video footage from meetings where MarineMap was used, and analysis of the application’s log files.

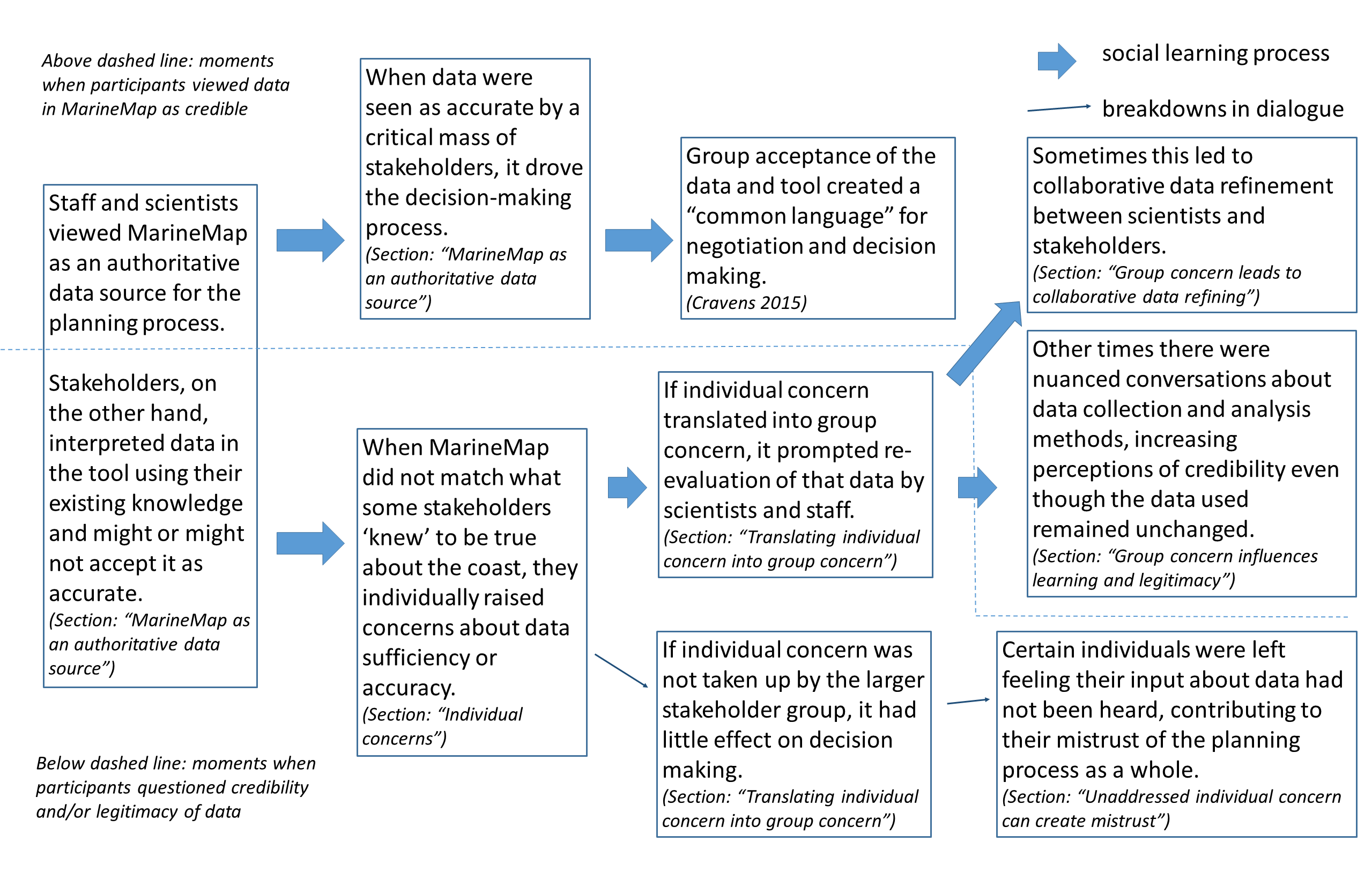

The paper explores how scientific data in decision support tools, like MarineMap or SeaSketch, come to be seen as credible by stakeholders and considers what happens in participatory decision making when a designated “authoritative” data source does not match stakeholders’ experiential knowledge. Amanda and her co-author Nicole Ardoin argue that authoritative data sources should be seen as the outcome of a social learning process, as well as a technological object.

The paper presents a framework (pictured below) suggesting that the presence or absence of group learning determines whether individuals’ concerns about data quality influence trust in decision making. When scientists and stakeholders had detailed conversations that were “open and listened to both sides,” trust and credibility resulted, whether or not the stakeholders’ or scientists’ views about the data ultimately prevailed. However, when individuals did not feel heard in such conversations, they left the process feeling distrustful of the scientific data being used for decision-making and, by extension, of the MLPA process itself.

This research suggests that conversations about data, and how they are generated, anchor the development of trust, which is important not only in the planning phases, but also in helping determine how those in surrounding areas will interact with protected areas once those areas are established. Scientists, stakeholders, managers, and conveners of participatory decision-making processes form learning communities in which the ways that conversations about data accuracy are conducted influence the success of the decisions being made.

Amanda Cravens is a Research Social Scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey. The research described in this blog post was completed while she was a researcher at Stanford University. Nicole Ardoin is an Associate Professor at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education and a Senior Fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment.