McClintock Speaks to National Academy of Sciences

Will McClintock spoke to memebers of the National Academy of Sciences, Division on Earth & Life Studies Committee in Washington, DC. On April 23, 2012, the National Academies assembled a small group of experts to advise the Division on Earth & Life Studies Committee on science and technology that enables bottum-up approaches to achieving science goals. Guest spearkers included Beth Noveck (New York Law School), Daniel Goroff (Sloan Foundation), Robert Gilmore (Qualcomm), Eric Paulos (Carnegie Mellon University), David van Sickle (Reciprocal Labs) and myself. Topics ranged from the role of open government and crowd-sourced research, sensor and communication technologies and strategies for a participatory culture. I was asked to speak about SeaSketch and collaborative geodesign.

In all honesty, I was unsure of how well my message would be received. This is the premier scientific body in the United States whose members include more than 300 Nobel laureates. I was there to tell them that their science was incredibly important for the decisions we, as a society, need to make about how we manage environmental resources. But I was also there to remind them that, no matter how good their science is, some people will want to reject it in favor of less science-based decisions - and this is OK. How does this make sense? If we want to manage our environmental resources intelligently and sustainably, shouldn't we simply let our most brilliant scientists simply call the shots? If they use objective methods, subjected to rigorous peer review, won't this lead to the best decisions?

That, of course, depends on what is meant by the "best decisions," and we had a very rich conversation about that very topic. I told the story about California's attempt to establish marine protected areas from 1999-2004. During that time, a team of our top scientists from California used sophisticated modeling techniques to identify areas in California state waters where marine protected areas should go, protecting key habitats and reducing the impacts of commercial and recreational fishing. By objective measures, these were excellent plans, supported by the best scientific information of the day. And yet, the public rejected these plans for a number of reasons which ultimately boiled down to this: many members of the public didn't trust the science or didn't feel as though their interests were sufficiently represented in the final decision.

So, despite the best attempt by top oceanographers, marine ecologists, fisheries biologists and economists, the "best decisions" were thrown out and California had made no progress toward establishing better ecological protection for its ocean.

What if scientists played an advisory role, one where they offered their opinions about the methods for establishing an ecologically coherent network of marine protected areas, the best scientific information, and a rigorous analysis of proposals offered by members of the public with little or no background in science? Would average citizens create scientifically defensible plans for marine protected areas?

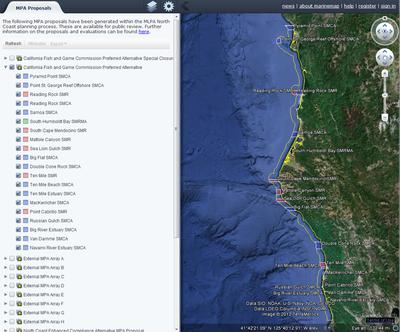

That was the experiment set in motion by California's Marine Life Protection Act Initiative, a public-private partnership that tasked California stakeholders (fishermen, conservationists, artists, teachers, politicians, surfers) with drawing up plans for new marine protected areas. In this process, the Science Advisory Team (SAT) did not submit plans, they simply evaluated the maps drawn by members of the general public using MarineMap, a web-based decision support tool that reflected the best available scientific information.

How did the plans drawn by members of the public stack up against those drawn by scientists in previous rounds? They were different in two ways. Members of the public drew up plans that had less protection for some ecosystems and, interestingly, had a greater impact on certain fisheries. From a purely scientific perspective, the plans were not as "good." On the other hand, they were signed into law by the Fish and Game Commission, protecting approximately 15% of California's ocean. Maybe these weren't the best plans, but they were a lot better than no plans at all, right?

What if the general public had simply trusted scientists to make the best decision? What sense does it make for non-scientists to scrutinize the work of our bests scientists? Generally speaking, scientists have a greater capacity to evaluate the research of other scientists than do members of the general public. Science is often technical and difficult to understand, even for those who think of themselves as smart, educated and motivated to learn. Try as I might, I'm never going to wrap my head around, say, the types of inflammasomes that are differentiated by their protein constituents, activators and effectors. It's beyond me. Shouldn't we just let the experts do their job?

Sometimes, yes, and sometimes no. Sometimes, the skepticism expressed by non-experts leads to better science. Fishermen in California, for example, objected to the simplistic fisheries models used by scientists to evaluate the economic impacts of proposed marine protected areas. This lead economist Chris Costello and colleagues to seek funding and develop dynamic fisheries models that more accurately predicted impacts to fisheries.

The ultimate solution to making good decisions around managing environmental resources, it seems, is developing mechanisms for average citizens to express their opinions, measure these opinions with science-based metrics, and facilitate conversations pertaining to scientific information. People feel better having expressed their opinions, learned something about the science used in decisions, and contributed to the plans we make.

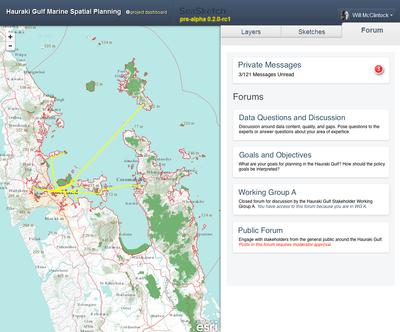

SeaSketch, a web-based application we are developing in my lab, is meant to address this problem. By using simple drawing tools, anyone with an Internet connection can draw any spatial plan (e.g., marine protected areas, transportation routes, energy extraction sites) and evaluate those plans using the best available scientific information. Using communication and collaboration tools, average citizens can create plans, scrutinize data, contribute information, encourage better science and, ultimately, have ownership of the decisions we make about our natural resources.

This application, and collaborative geodesign tools as a whole, stand to dramatically improve our ability, as societies, to use science and engage members of the public to make wise, place-based decisions.